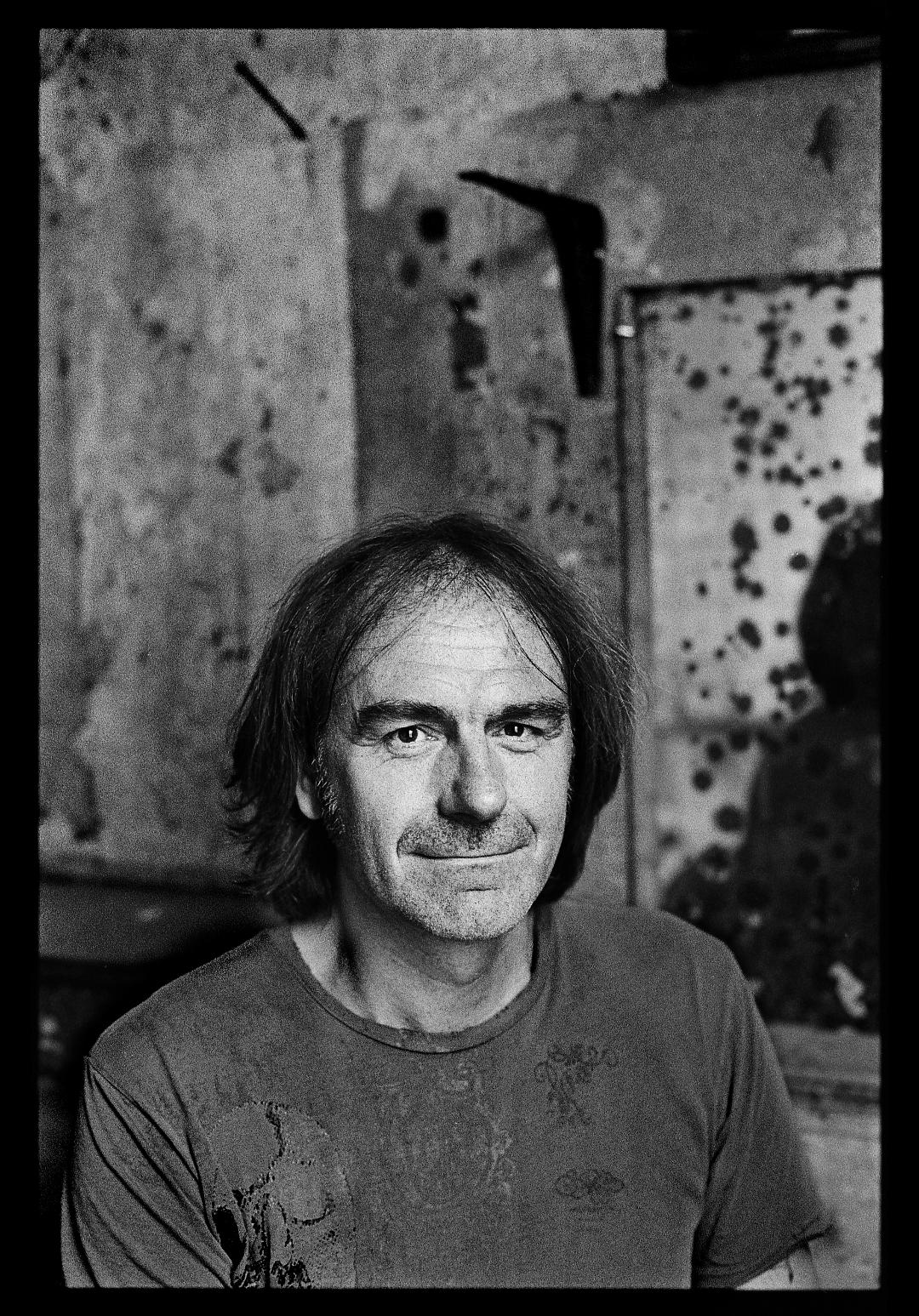

© Martin Menke

Benoît Debie (2022)

The Eye of the Spectacle

Opening our eyes to the here and now and to the zeitgeist. Edgy, intense, sensual. Benoît Debie’s camerawork is a formative part of the cinema of the 2000s. We’re paying homage to his artistic and empathetic approach to framing his shots, which gives the viewer goose bumps and a warm feeling inside.

People who work behind the camera often blend into the background and remain largely unknown as a result. The spectacular artistry of Benoît Debie's camerawork is so unforgettable and incomparable, however, that everyone ought to be familiar with it. The way Debie frames his images and uses colour, light and motion have earned him a reputation far beyond his home country, Belgium, as a master of his craft.

These are memorable and rapturous images, sleepwalking compositions that give rise to fantasies that take us far away. In psychological thrillers, dramas and documentaries alike, his camerawork is agile and versatile, but most of all, it is highly empathetic. It reveals the slightest hint of emotion in facial expressions and gestures. The dynamism that Debie matches to the music and sounds in many films says something about the present state of the media; it evokes trends – such as the cult of the supposedly authentic – and acknowledges them with a touch of irony.

Debie’s work is inextricably linked to that of director Gaspar Noé, with whom he has created an impressive and multi-faceted oeuvre. Starting with Noé’s second feature film, ›Irreversible‹ (2002), a trippy nightmare like no other, Debie has been involved in all of Noé’s feature films, from a drug trip in Tokyo (›Enter the Void‹, 2009) to ›Love‹ (2015) and ›Climax‹ (2018), to a meditative look at dying in ›Vortex‹ (IFFMH 2021). He has been instrumental in boosting the career of Fabrice du Welz, a Belgian master of thrillers and fantasy (›Calvaire‹, ›Vinyan‹ and ›Colt 45‹); he has also rejuvenated the work of veteran director and IFFMH alumnus Wim Wenders (›Submergence‹, ›The Beautiful Days of Aranjuez‹, ›Everything Will Be Fine‹). In the process, he has brought such stars as Alicia Vikander, Charlotte Gainsbourg and James McAvoy into the limelight. He directed Joaquin Phoenix and Jake Gyllenhaal in Jacques Audiard’s meta-western ›The Sisters Brothers‹ and collaborated with Ryan Gosling on his directorial debut, ›Lost River‹.

Debie also directed Harmony Korine’s ›Spring Breakers‹ and ›The Beach Bum‹; he and Hollywood auteur Andrew Dominik shot ›One More Time with Feeling‹ (2016), a melancholic black-and-white documentary about Nick Cave. He has directed music videos for Beyoncé, Rihanna, JackBoys & Travis Scott, John Legend, SebastiAn and Stromae, among others.

What’s special about Debie’s artistic style of creating images is undoubtedly the fun that’s involved: the fun he has impressing people, the fun of putting his camera in places and positions that are unusual and surprising, that afford us new perspectives and impressions that are quite simply beyond anything we’re familiar with. This is cinema in the best sense of the word: a spectacle and a challenge to viewing habits, with a desire for excess and an openness to everything that makes people tick: their desires, their fears and their dreams. The fact that he never loses sight of the vulnerability of the actors and characters in front of his lens, but always gently turns the spotlight on this vulnerability, makes him the master of humanism that the world needs. Benoît Debie is leaving an overwhelming mark on cinema. And we love the films whose images he creates, as idiosyncratic as they are; no, precisely because they are so idiosyncratic.