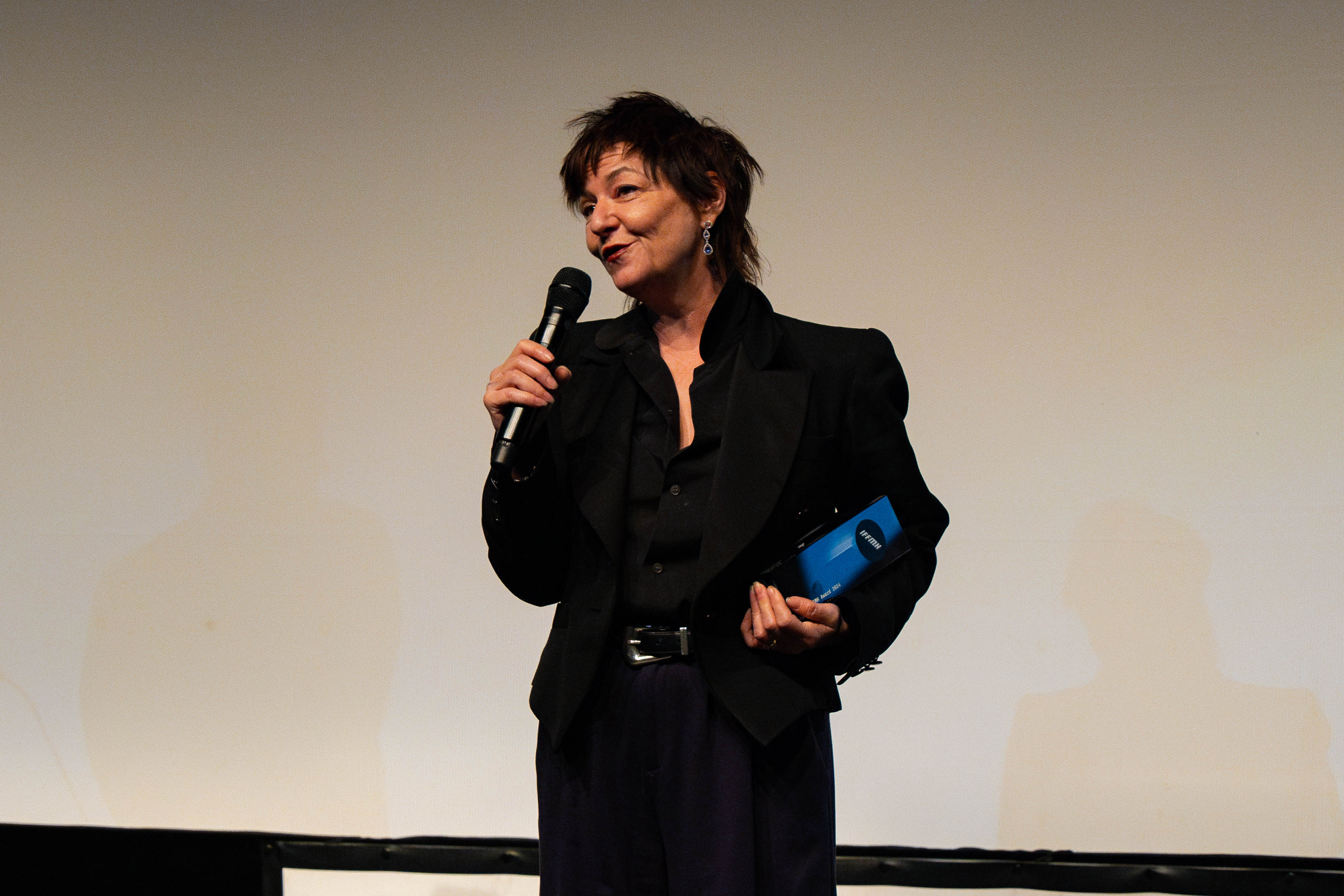

In 2024, Scottish director Lynne Ramsay was the recipient of our Grand IFFMH Award. With ›Ratcatcher‹, ›We Need to Talk About Kevin‹ and ›You Were Never Really Here‹, three outstanding films from her oeuvre were screened once again at our festival. In a masterclass, the renowned filmmaker provided insights into her work and her cinematic visions. Visitors were then able to engage in conversation with Lynne Ramsay during an open question and answer session.

Lynne Ramsay

awarded with the Grand IFFMH Award 2024

Lynne Ramsay

Lynne Ramsay’s characters never feel at home. They can’t come to terms with themselves. They are restless. These feelings are transmitted to us. Lynne Ramsay’s films offer us no respite. And how could they – right at the beginning, a boy drowns (›Ratcatcher‹, 1999), a young woman wakes up next to her boyfriend’s corpse (›Morvern Callar‹, 2002), we are faced with the red of violence and the menace of a dramatic soundtrack (›We Need to Talk About Kevin‹, 2011), or with Joe gasping for air, a plastic bag over his head (›You Were Never Really Here‹, 2017). Without digressing, her works confront us with a trauma and instantly captivate us.

In her short films ›Small Deaths‹, ›Kill the Day‹, and ›Gasman‹, Ramsay already developed some of her central themes, including childhood, loss, and memory, as well as trademark techniques such as storytelling via allusion and ellipsis. These immediately earned her several major awards. Then came her debut feature ›Ratcatcher‹, which won a BAFTA, the British film award. As always in her films, the main character is confronted with an extreme situation, whose repercussions touch on universal aspects of human existence, in this case the guilt complex: the child protagonist is partly responsible for the drowning of another boy. ›Morvern Callar‹ explores how the title character deals with her grief following the suicide of her partner. In ›We Need to Talk About Kevin‹, these two themes – guilt and grief – merge in the mother’s perception of her psychopathic son and his actions. Her latest film, ›You Were Never Really Here‹, clearly brings these universal complexes together in one character. Joe, the brutal hitman played by Joaquin Phoenix, is doubly traumatized: he is both victim and perpetrator.

Even more than stories that are at once extreme and universal, it’s Lynne Ramsay’s unmistakable aesthetic that cemented her exceptional reputation. Images and compositions take precedence over words. And even if the stories are big and tragical, the storytelling is free from any pathos. It always withholds essential information from us. The framing, for example, often shows people only in parts. The result is a great openness to interpretation. This also includes the use of almost emblematic close-ups that are left to speak for themselves, be it a slice of bread crawling with ants, the scars on Joe’s body, or the leitmotif-like repetition of certain gestures and colors. And let’s not forget the close-ups of faces and the emotions they express – especially in the case of the child actors, these are absolutely incredible. Many facets of the story are told this way, indirectly, inviting us to discover them for ourselves.

The leitmotif technique also points to the importance of music in Ramsay’s films. Just as entire sequences often derive their rhythm from music, others – ›We Need to Talk About Kevin‹ is a particular highlight in this regard – make use of a compositional technique that interweaves different time strands like musical voices. It’s a technique that is also linked to trauma: traumatized people are never really there, they can’t simply live in the here and now, the present only exists for them alongside the traumatic past, its constant memory. This enduring presence of trauma is conveyed in ›You Were Never Really Here‹ less through composition than via Joe’s stooped, scarred body.

Lynne Ramsay’s characters never feel at home. At the same time, her films never allow us to fully settle inside her world. Her often black humor, her irony – or even a mouse floating away into space on a balloon – create distance. Like the compositional techniques, this distance from the action grants us insight into the psyche of traumatized characters and their own distance from the world. In a way, the cinematic poetry of trauma becomes the trauma of poetry. And this despite the fact that the acts of violence themselves are almost completely left out.

Lynne Ramsay’s wonderful films therefore don’t offer respite even in retrospect, never again, they burn themselves into us. And that’s a good thing. Where would we be without them?